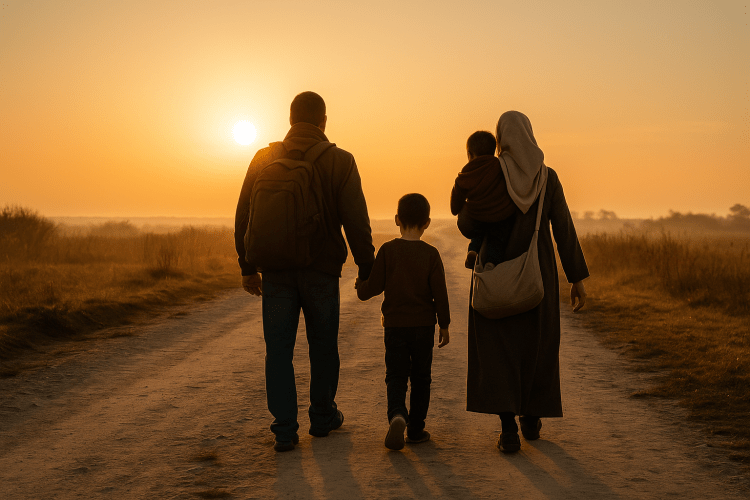

As I watched news after news of Syrian refugees returning home after years of displacement, several memories crossed my mind. Each, a stark reminder of the intrinsic value people everywhere attach to their roots. It echoed an old African adage: a foreign land full of luxury can never be the same as home.

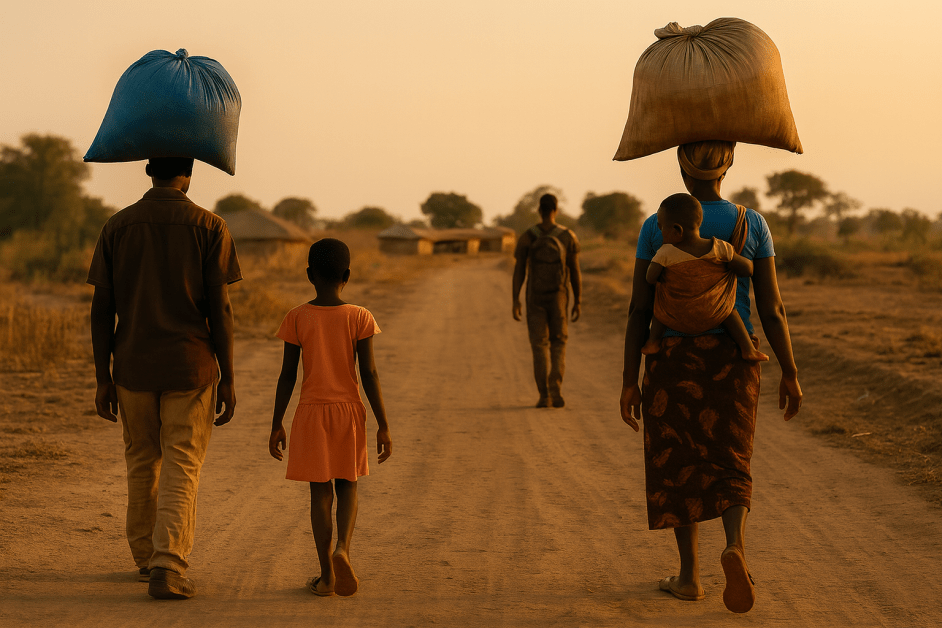

The statistics don’t always tell the refugee crisis story. Too often, the global image of a refugee is someone escaping their homeland for Europe or North America, hoping to start a better life. But that is a narrow and often, a misleading portrait. The majority of refugees do not cross oceans or continents in search of luxury; they flee because survival demands it.

According to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), about 67% of forcibly displaced people flee to neighboring countries, and 73% are hosted by developing or poorer nations. In 2024 alone, 9.8 million displaced people returned home. This is a reminder that their goal is rarely to “find a better life in the West,” as popular narratives suggest. It is, first and foremost, to find safety. And, when possible, to return home.

The Many Faces and Causes of Forced Migration

The causes of forced migration are as complex as the people it affects. They range from war and persecution to environmental disasters, political instability, and even harmful cultural or religious practices. To speak of “refugees” as one group with a single experience is to erase the diversity and depth of their realities.

For some, displacement is generational. Many who are called refugees have never actually lived in the country listed on their birth certificates. They were born and raised in camps, far from a homeland they know only through stories. And even where that homeland lies just across a border—like Ghana to Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, or Sierra Leone, or Ukraine to Moldova—in times of war or turbulence, home can feel much farther away, like a romantic longing or a fading mirage.

Closer to Home: A West African Perspective

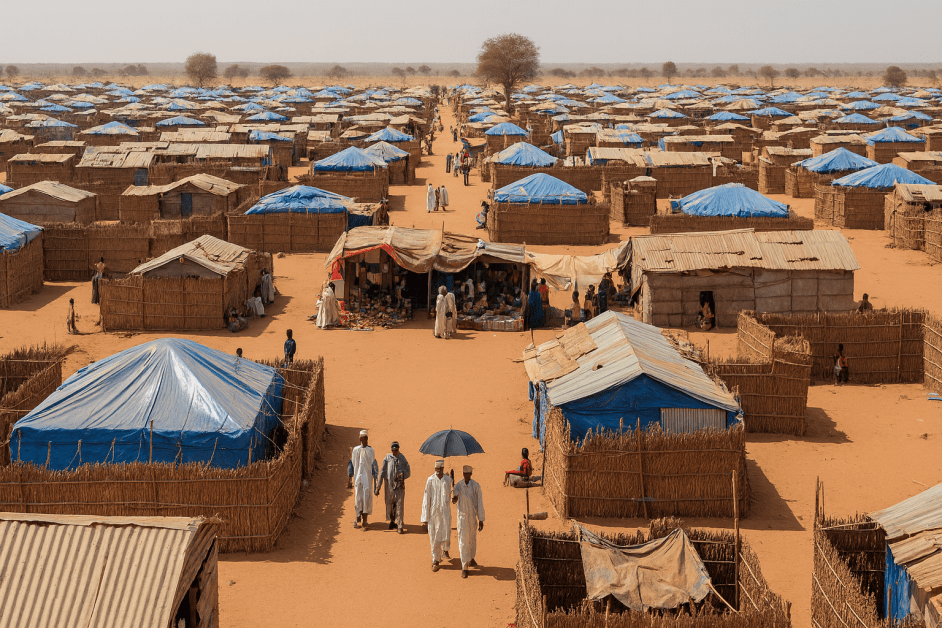

In the early 2000s, Ghanaians in Accra began seeing unfamiliar faces along busy city streets. These people were men, women, and children with tanned skin and curly hair, begging for alms. They were from neighboring African nations, Chad and Sudan, driven southward by drought, conflict, and political collapse.

Their plight was a stark reminder that most refugees move within regions, not across continents. Many of those who fled never returned home. Decades later, some of their children have grown up in Ghana, speaking local languages, blending into urban life, yet still bearing the invisible identity of displacement.

When civil war broke out in Liberia under Samuel Doe’s regime, neighboring West African nations: Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Ghana, opened their borders to hundreds of thousands of Liberian refugees. The same was true of the Sierra Leonean conflict that followed. Although a small fraction eventually reached the United States or Europe, the overwhelming majority found refuge right next door, in countries equally burdened by poverty and political uncertainty.

Behind the Numbers: Lives Interrupted

Numbers rarely show the faces behind them. Families torn apart, careers ended abruptly, childhoods rewritten by fear.

I remember one Sierra Leonean couple I met in Accra during the war. They were young, educated, and newly married. He, a government official; she, a bright, curious woman and a college graduate. I was still in high school then, and our common experience instantly connected us. She was eager to talk about boarding school life in our two countries, which shared many similarities.

They managed to rent a single room in a crowded compound house in Osu, a lively neighborhood. They shared bathrooms, fetched water with others, and lived simply, but with dignity.

Unlike those who ended up in camps or on the streets, they adjusted remarkably well to their new environment. Their greatest hope, though, was to go back home to rebuild and reclaim the life they had left behind.

That longing for home is universal among displaced people. Even in their most comfortable states, where food and basic supplies are adequately provided, the one thing most refugees desire most is to return home. Refugee camps may provide safety, but they rarely replace belonging. When the guns fell silent in Liberia, thousands of Liberians in exile made their way back to their war-ravaged homeland, despite the devastation that awaited them. For many, the journey home was as perilous as the one that took them away, yet it symbolized freedom in its truest form. It was the right to stand again on one’s own soil.

The Refugees We Don’t Talk About

Not all forms of forced displacement cross national borders. In my years as a journalist, I encountered people who were refugees within their own countries. People trapped not by war, but by culture.

On a field assignment in Ghana’s Volta Region, my colleague and I visited a shrine where women were kept in servitude to atone for crimes allegedly committed by family members. The practice, known as Trokosi, had been legally abolished in 1998 but persisted in secret. Women, some born into bondage, lived as “wives” to the priest, cut off from their families and stripped of basic human rights.

Amnesty International and other human rights groups had intervened, using a combination of advocacy, community engagement, and economic support to dismantle the system. The most profound part of their work wasn’t only freeing the women. It was also ensuring that the priests themselves were not left destitute. By addressing the economic roots of the practice, resistance decreased, and entire shrines gradually released the women.

I will never forget the happy faces of those women who regained their freedom and reintegrated into society—some for the first time in decades—equipped with tools and resources to rebuild their lives. It was liberation in the truest sense.

Beyond Refugee Camps

The UNHCR’s mandate has evolved over time. Once focused solely on refugees, it now includes internally displaced persons (IDPs), stateless people, and others living in refugee-like conditions. These are individuals who may never cross a border but face the same vulnerabilities: loss of home, safety, and identity.

It makes no difference whether people live in camps across borders or shrines within their own village; displacement strips them of control over their own lives. Understanding that truth is the first step toward reshaping the world’s narrative on refugees.

A Shared Responsibility

The refugee story is not about numbers, nor about the West versus the rest. It is about human beings caught in circumstances they did not choose, seeking what every person deserves — safety, dignity, and the right to begin again.

Until the global conversation shifts from counting refugees to understanding them, we will continue to miss the essence of what forced migration truly means.